- You are here:

- Home »

- Educational

Category Archives for Investing

A Financial Maverick @ Work

Once upon a time in a jungle village not so far away, a man appeared and announced to the villagers that he would buy live and healthy monkeys for $10 each.

Since the villagers considered the monkeys a real nuisance, many of them went into the jungle and began setting traps to catch them. The man bought thousands of monkeys at $10 and, as supply started to diminish, the villagers reduced their efforts. When this happened, the man announced that he would now buy monkeys at $20 each.

This reinvigorated the villagers efforts and they started trapping monkeys again. Gradually the number of free monkeys diminished even further making hunting efforts much more challenging and time consuming – people started going back to their farms. The offer was increased to $25 each, until it was difficult to find even a single monkey, let alone catch it!

The man then announced that he would buy monkeys at $50 each! However, since he had to go to the city on some business, his assistant would now buy on his behalf. As soon as the man was off on his journey, the assistant let the villagers in on a secret. He invited all the hunters and their relatives to have a look at the monkeys in the big cage that the man had paid for. And then he made them an offer that they simply could not refuse.

“I will sell them to you for $35 and when the man returns from the city, you can sell them to him for $50 each as he promised.”

The word spread like wild fire and before long, most of the villagers gathered their savings and managed to buy every single monkey held captive in the massive cage before releasing them into the jungle so that the hunt could begin anew.

They never saw the man nor his assistant again.

In the above article the names were changed to protect the innocent. The ‘financially sound’ structured products were represented by monkeys in the story but the facts remain the same; this was no accidental occurrence it was simply a version of the now popular Ponzi game. You probably already know this but, a ponzi scheme is a scam where the perpetrator collects money from new investors and uses these new cash inflows to pay high returns to past investors, so that these influencial existing investors believe that their capital is intact and working for them. All the while, the scam artist has been spending the initial capital on himself rather than investing it as advertised. To attract a special breed of greedy investor, such schemes often are promoted as exclusive clubs as in ‘by invitation only’ thus toying with the wealthy and famous have-it-alls psyche to the point where they absolutely must be part of this exclusive ‘winners circle’ in order to maintain their image.

Reality vs. Technology Bubble You Decide

This was too entertaining to pass up so I just had to share it with you. Did you ever wonder about all that hype regarding a technology bubble? It seems that companies can create incredibly advanced technology yet, if the market perceives it in any sort of negative way, the product (regardless of how good it is or how many problems it solves) does not stand a chance to succeed. On the other side of the spectrum, you have large multi-national companies that produce less than adequate products (Microsoft Vista is a good example of this) but they manage to push the products into the market and then reap the rewards of success partly due to their talented marketing team’s efforts in self promoting by creating enough buzz to fool the market into believing that the product is a raving success. Amazing, yet scary – all at the same time. If you would like to know more about making your products a raving success, let us know your thoughts.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YuAJHaXKgFk

Investment Evaluation Guidelines

I have been asked many times for a guideline when it comes to evaluating investments that we (or our Clients) make. People ask why we invested in Company X and not in Company Y, Why are we interested in industry A more than industry B etc.

Well, the simple truth is that we invest to win.

We tend to strip out a lot of soft factors and focus on results.

Did management deliver?

Can they do it again?

A lot of investment decision making is based on an understanding of industry trends, a trusted relationship with players that perform consistently above industry average and some form of defensible proprietary technology that is in demand because it solves a specific pain for a given market segment.

If a company has a specific target market segment in their crosshairs, we know that they have done their homework – when management states that they serve all industries, our alarm bells start ringing.

Following is my personal guideline for what really counts when considering investment in a startup or early stage company.

1) Market potential

2) The Team

3) Results

4) USP

Investment Process

- The success of investment in an early stage company depends on people and their ability to execute on a detailed business plan, therefore a lot of emphasis is placed on the team.

- The structure of the investment is vital and requires creative and often complex terms.

- Pricing is a key factor which needs to be carefully analyzed and negotiated.

- An interesting exit strategy is required in order to maximize a timely return.

Investment Selection

- Management Team: Experienced, in-depth knowledge of business, results oriented.

- Innovative Products/ Proprietory Technology: Highly differentiable, superior, specialized expertise, meets market needs.

- Business Plan/ Milestones: Well thought out business plan including milestones and contingency plans.

- Substantial Investment Position: Ability to obtain a substantial investment position, influence the selection of executive management and the strategic direction of the company.

- Valuation: Negotiate and obtain a fair pricing structure.

Initial Investment Valuation

- Underlying industry assumptions

- Realistic income statement over 3-5 years

- Competition

- Major criteria:

- Technology value

- Capital requirements

- Market potential

- Capital structure

- Operational cash flow

Determination of NAV for privately held startup companies

- The original cost: An approximation of the fair market value at the time of the transaction.

- Write off: NAV calculation at cost, less any write-off deeemed necessary if subsequent performance fails to meet business plan forecast.

- Capital increase: NAV calculation in principle based on the capital increase price, less 10% to 29% discount if deemed necessary based on valuation factors.

- Write up: A write up is recognized when a significant event occurs such as increased profitability and achievement of milestones.

The Next Big Thing

I spent a good amount of time reviewing business opportunities in China both locally and from abroad in 2006/7. The overwhelming conclusion I drew was that there is enormous potential in almost every sector of the economy driven by both foreign demand and local consumption capacity. Some companies were not able to produce enough product to satisfy local and regional demand let alone national demand in China yet, as I stepped into the reality that is the China of today, I discovered that I needed to shed my preconceived ideas that China’s production capacity exists to serve foreign interests. Sure, international markets are of great importance to the Chinese manufacturing sector but, the number of companies I reviewed that produced product for export only were few and far between.

China is a gigantic market just getting ready to shift into a consumer oriented phase. So, what exactly was I doing in China? Well, I figured that if I could identify sectors with the strongest production growth this would give me some insight into a future global trend that helps to answer my number one question… what is going to be the next big thing? and… how can I come up with a best guess estimate before the world wakes up and smells the coffee?

So here is what I did. I reviewed the following industries and their largest manufacturing partners in China.

Lighting: including LEDs and Displays

Optics: lenses of all shapes and sizes including x-ray… yes, x-ray lenses!

Sensors: the kind that are able to sense 5 particles per million for security applications fighting potential terrorist threats

Actuators: MEMS, NEMS MOEMS and NOEMS… don’t even ask plus medical testing devices

Storage: mechanical HDDs are on their way out or are they? I had a 100 GB solid state drive in my hand

Semiconductors: What is the biggest obstacle to progress on Moore’s law these days… I found out!

Energy: Well, with the rising price of fossil fuels alternative is the only way and improving methods of harvesting energy were on the list of the coolest inventions I saw

Biotech or as it’s known today… life science – DNA manipulation seems to be all the rage but what caught my attention was the ability of some companies to grow skin and…

Ok, enough! if I haven’t bored you by now you are probably wondering what this article is all about.

Well, I thought that if I were able to analyze what is being produced today and get an idea of what is coming down the pipe to satisfy the needs of tomorrow then I could gain some valuable insight into who will manufacture the next big hit for tomorrow… for several different industries and kind of hedge my bet. I got lucky, I discovered something even more valuable.

In my research I analyzed all major players in the above industry sectors and put together something like a roadmap for each. Although the time lines vary as each company plans to move its invention from the R&D phase into production and no one is able to forecast consumer or business demand for 5 years from today, there were some very interesting correlations. One was size. Products will be getting smaller – fact. Another was that products will be influenced more by market need (pull) rather than an inventor’s desire to create a new market (push). Lastly, ROI is playing a greater role in how long a particular invention is allowed to cook in the R&D labs before it is forced out the door to an awaiting and already expectant consumer market.

How about a summary of my thoughts? OK, take the current products manufactured today, do research on where they are headed, look into the components that enhance or add value to each of these products and see if there are a few companies that produce the next generation of these components – then limit the study to less than 10 industries where these components are bound to have major impact.

Do you see where I am headed with this now? If I can identify companies that produce something really small on a micro or even nano scale that improves today’s products and will be integral in moving tomorrow’s products forward, I will have successfully identified a winner in not one but several industries.

In my most recent estimation, there are not a lot of these players out there but they do exist and I am hunting them down one by one. Did I mention that I am already in discussions with one?

Yes, I believe that I have identified the first of several of these core component providers. If you have read my article this far, then you may want to contact me to learn more because information this hot, can not yet be published in an open forum. Alas, the search continues and a new project is born to narrow down the hunt for the next big thing.

Creating an Executive Summary

Most guides to writing an executive summary miss the key point: The job of the executive summary is to sell, not to describe.

The executive summary is often your initial face to a potential investor, so it is critically important that you create the right first impression. Contrary to the advice in articles on the topic, you do not need to explain the entire business plan in 250 words. You need to convey its essence, and its energy.

You have about 30 seconds to grab an investor’s interest. You want to be clear and compelling.

Forget what everyone else has been telling you. Here are the key components

that should be part of your executive summary:

1. The Hook

Lead with the most compelling statement of why you have a really big idea. This sentence (or two) sets the tone for the rest of the executive summary. Usually, this is a concise statement of the unique solution you have developed to a big problem. It should be direct and specific, not abstract and conceptual. If you can drop some impressive names in the first paragraph you should – world-class

advisors, companies you are already working with, a brand name founding investor. Don’t expect an investor to discover that you have two Nobel laureates on your advisory board six paragraphs later. He or she may never read that far into your doc.

2. The Problem

You need to make it clear that there is a big, important problem (current or emerging) that you are going to solve, or opportunity you are going to exploit. In this context you are establishing your Value Proposition – there is enormous pain and opportunity out there, and you are going to increase revenues, reduce costs, increase speed, expand reach, eliminate inefficiency, increase effectiveness, whatever. Don’t confuse your statement of the problem with the size of the opportunity (see below).

3. The Solution

What specifically are you offering to whom? Software, hardware, service, combination? Use commonly used terms to state concretely what you have, or what you do, that solves the problem you’ve identified. Avoid acronyms and don’t try to use these precious few words to create and trademark a bunch of terms that won’t mean anything to most people. You might need to clarify where you fit in the value chain or distribution channels – who you work with in the ecosystem of your sector, and why they would be eager to work with you. If you have customers and revenues, make it clear. If not, tell the investor when you will.

4. The Opportunity

Spend a few more sentences providing the basic market segmentation, size, growth and dynamics – how many people or companies, how many dollars, how fast the growth, and what is driving the segment. You will be better off targeting a meaningful percentage of a smaller, well-defined, growing market than claiming a microscopic percentage of a huge, heterogeneous, mature market. Don’t claim you are addressing the $24 billion widget market, when you are really addressing the $85 million market for specialized arc-widgets used in the emerging nano-sprocket sector.

5. Your Competitive Advantage

No matter what you might think, you have competition. At a minimum, you compete with the current way of doing business. Most likely, there is a near competitor, or a direct competitor that is about to emerge (are you sufficiently paranoid yet??). So, understand what your real, sustainable competitive advantage is, and state it clearly. Do not try to convince investors that your key competitive asset is your ‘first mover advantage.’ Here is where you can articulate your unique benefits and advantages. Believe it or not, in most cases, you should be able to make this point in one or two sentences.

6. The Model

How specifically are you going to generate revenues, and from whom? Why is your model leverageable and scalable? Why will it be capital efficient? What are the critical metrics on which you will be evaluated – customers, licenses, units, revenues, margin? Whatever it is, what impressive levels will you reach within three to five years?

7. The Team

Why is your team uniquely qualified to win? Don’t tell us you have 48 combined years of expertise in widget development; tell us your CTO was the lead widget developer for Intel, and she was on the original IEEE standards committee for arc-widgets. Don’t just regurgitate a shortened form of each founder’s resume; explain why the background of each team member fits. If you can, state the names of brand name companies your team has worked for. Don’t drop a name if it’s an unknown name, and don’t drop a name if you aren’t happy to give the contact as a reference at a later date.

8. The Promise

When you are pitching to investors, your fundamental promise is that you are going to make them a boatload of money. The only way you can do that is if you can achieve a level of success that far exceeds the capital required to do that. Your Summary Financial Projections should clearly show that. But if they are not believable, then all of your work is for naught. You should show five years of revenues, expenses, losses/profits, cash and headcount. You should also show a key driver or two, such as number of customers and units shipped each year.

9. The Ask

This is the amount of funding you are asking for now. This should generally be the minimum amount of equity you need to reach the next major milestone. You can always take more if investors are willing to make more available, but it is hard to take less. If you expect to be raising another round of financing later, make that clear, and state the expected amount.

You should be able to do all this in six to eight paragraphs, possibly a few more if there is a particular point that needs emphasis. You should be able to make each point in just two or three simple, clear, specific sentences.

This means your executive summary should be about two pages, maybe three. Some people say it should be one page. They’re wrong. (The only reason investors ask for one page summaries is that they are usually so bad the investors just want the suffering to be over sooner.) Most investors find that there is not enough information in one page to understand and evaluate a company.

Please remember that the outline above should not be applied rigidly or religiously. There is no template that fits all companies, but make sure you touch in each key issue. You need to think through what points are most important in your particular case, what points are irrelevant, what points need emphasis, and what points require no elaboration.

Some other general points:

- Do not lead with broad, sweeping statements about the market opportunity. What matters is not market size, but rather compelling pain. Investors would rather invest in a company solving a desperate problem for a small growing market, than a company providing an incremental improvement for a large established market.

- Drop names, if they are real; don’t drop names if they are smoke. If you have a real partnership with a brand name company, don’t hide your lantern under a bushel basket. If you consulted for Oracle’s HR department one week, don’t say you worked for Oracle.

- Avoid ‘purple farts’ – phrases and adjectives that sound impressive but carry no substance. ‘Next generation’ and ‘dynamic’ probably don’t mean anything to your readers (unless you are talking about DRAM) and tend to be irritating. Everybody thinks their software is ‘intelligent’ and ‘easy-to-use,’ and everyone thinks their financial projections are ‘conservative.’ Explain your company the way you would to a friend at a cocktail party (after one drink, not five).

- State your value proposition and competitive advantage in positive terms, not negative terms. It is what you can do that is important, not what others cannot do. With the one or two most obvious competitors, however, you may need to be very explicit: ‘Unlike Oracle’s sprocket solution, our software can operate…’

- Use simple sentences, not multi-tiered compound sentences.

- Use analogies, as long as you are clarifying rather than hyping. You can say you are using the Google model for generating revenues, as long as you don’t say you expect to be the next Google.

- Don’t lie. You would think this goes without saying, but too many entrepreneurs cross over the line between passionate enthusiasm and fraudulent misrepresentation.

Go back and reread each sentence when you think you’re done: Is each sentence clear, concise and compelling?

Finally, one of the most important sentences you write will not even be in the executive summary – it is the sentence that introduces your company in the email that you or a friend uses to send the executive summary. Your summary might not even get read if this sentence is not well-crafted. Again, it should be specific and compelling. It should sell your company, not just describe it. Venture investors are predisposed to like entrepreneurs. Many were entrepreneurs in prior lives, and all enjoy the challenge and excitement of starting up companies. Most are on your side. So please help them get to know you better by telling your story clearly and concisely.

VCs.. arrGH!

Many venture capitalists expect entrepreneurs to go out on a limb for them – climbing high while vigilantly sawing away at a supporting branch.

When Clients ask what exactly is needed for funding, I can provide some very interesting answers based on my 20+ years of experience… Here are some of my personal favorites:

An impeccable board of directors

It may not be the first issue you are faced with but this is one of the really important ones. Your board of directors needs to be comprised of a broad spectrum of very skilled individuals experienced in the industry of your company. The venture capitalist firms all look for a strong board and that means a board that brings in money (read Sales), investors and strategic relationships – all the important things you need as an early stage company.

A winning team

You may have a great idea, but if you don’t have a strong core team, investors aren’t going to be willing to bet on your company. Think of this as an analogy to a horse race. Betting on horse races equates to betting on high-tech. Betting on a race is equivalent to betting on the industry your company is in. Betting on a horse is like betting on your company to succeed and betting on a jockey is what a VC is after. VCs want to bet on winners that have proven their abilities before. The team surrounding the jockey is also key but don’t get too caught up in having everyone on board before chasing funds. You don’t need to have a complete, world-class, all-gaps-filled team. But the founders have to have the credibility to launch the company and attract the world-class talent needed to fill in the gaps. The lone entrepreneur, even with all the passion in the world, is never enough. If you haven’t been able to convince at least one other person to drink the lemonade, investors certainly won’t. One other thing… If the founders do not have skin in the game, don’t expect others to invest their savings. To be convincing, founders need to go out on a limb, risk their personal savings, sell their car or get a second mortgage on their home to indicate that they too have risked all to make this company a success.

A compelling idea

“Every entrepreneur believes his or her idea is compelling. The reality is that very few business plans present ideas that are unique. It is very common for investors to see multiple versions of the same idea over the course of a few months, and

then again after a few years. What makes an idea compelling to an investor is that it reflects a deep understanding of a big problem or opportunity, and offers an elegant solution.”

The market opportunity

You should be targeting a sector that is not already crowded, where there is a significant problem that needs to be solved, or an opportunity that has not been exploited, and where your solution will create substantial value. Contrary to popular belief, it’s not about how big the market is; it’s about how much value you can create.

The technology

VCs ask – What makes your technology so great?

The correct answer is, ‘There are plenty of Customers with plenty of money that want to buy it’.

If you have a technological advantage today, how are you going to sustain that advantage in the future? Patents alone won’t do it. You better have the talent or the partners to assure investors that you will stay ahead of the curve.

Competitive Advantage

Every interesting business has real competition. Competition is not just about direct competitors. It includes alternatives, ‘good enough’ solutions, and the status quo. You need to convince investors that you have advantages that address all these issues, and that you can sustain these advantages over several years.

Financial projections

Your projections demonstrate that you understand the economics of your business. They should tell your story in numbers – what drives your growth, what drives your profit, and how your company will evolve over the next 5 years.

Validation

Is there any evidence that your solution will be purchased by your target Customers? Do you have an advisory board of credible industry experts? Do you have a co-development partner within the industry? Do you have Customers or Beta users to whom investors can speak? Do you already have paying customers? The more credibility and Customer traction you have, the more likely investors are going to be interested.

What I have learned is that a company needs good scores in ALL of the above areas and excellent scores in at least 3 in order to have a reasonable chance to secure funding.

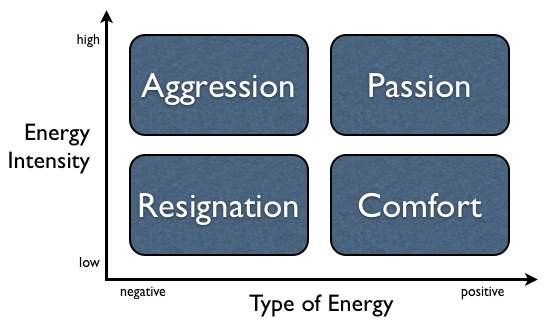

Corporate Energy

Yes, this topic is a bit on the esoteric side I admit… but hear me out, there is logic and reason behind the glass. Some colleagues of mine use the following model to judge a company’s investment worthiness. I found it fascinating and have now evaluated a few hundred firms using this technique. Situations at a few companies that I previously worked with made me feel uneasy about the company and its culture but I did not know why. Today, I have a good idea what triggered my feelings and I have come to the conclusion that unless I can change things for the better, I would rather not work with such firms again. These firms were suppliers of mine as well as a few Customers. Read on and assess the technique for yourselves – I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Energy zones

An organization’s energy can be perceived as either positive (driven by enthusiasm, pride, joy or satisfaction) or negative (guided by fear, uncertainty, frustration, doubt or sorrow). Most organizations fall into one of four categories:

1) Comfort 2) Resignation 3) Aggression and 4) Passion.

Companies in the comfort zone have a high level of satisfaction but a low level of action. Thus, its employees might be very content on the one hand but they lack the vitality, alertness, motivation and emotional tension necessary for initiating bold new strategic thrusts or significant change.

Organizations in the resignation area, on the other hand, show both low and negative energy. Therefore, they are not particularly active and their employees may not identify with the company goals at all.

Businesses in the aggression area are driven by a strong, negative energy, which often expresses in an

intense internal competitive spirit and portrays in high levels of activity and alertness. Hence, unlike organizations in the resignation area, they often direct all power towards achieving company goals. The analogy here is of a ping pong match where employees hit the ball back and forth across the net either to other team members or to Customers and partners and the net result is dissatisfaction since the ball keeps coming back and there is little forward momentum as a unit. Despite progress by a few successful individuals – it is not a team effort.

Lastly, firms in the passion zone flourish and excel on their great positive energy and large amount of varying activities. Their employees feel joy and pride working in the organisation and all enthusiasm and excitement appears to be set on reaching shared organisational priorities.

Organizations in the comfort or resignation zones live in the past and have basically given up. Consequently, they are less likely to be successful, as they prefer standardised, institutionalized ways of working. They shun innovation and risk as well as suffer from conflicting priorities and a lack of

employee commitment.

Companies in the aggression or passion zones show urgency for productivity as they strive for larger-than-life goals. Their energy moreover supports them in aligning and channelling their powers and in directing them towards common goals and activities.

In short, the model suggests that high achieving organisations are full of energy. Businesses that work from a basis of passion or with passionate people for that matter, are likely to have the highest energy levels. Their work is not only driven by very positive factors but they do a lot to develop themselves and their people, too. Simply put, their cultures appear to be based on cohesion. The analogy here is of a football team (soccer for you folks in the USA) where the team has a common goal and each member knows his role within the team so that as a unit they are able to move the ball forward and achieve their goals together.

Valuation Algebra

Ever wonder why many smart investors are able to calculate valuations and other investment related numbers in their heads? During deal negotiations, this used to both amaze and confound me until a good friend explained the process in terms that almost anyone can understand. It took me a while but I think I can safely say that even sophisticated entrepreneurs don’t grasp how valuation math works. VCs talk about pre-money, post-money, and share price as though these were universally defined terms that the average citizen is expected to understand. To ensure that everyone is talking about the same thing, I started forwarding the following explanation. Folks, this is about the math behind the calculations, not the philosophy of valuation.

In a private equity or venture capital investment, the terminology and mathematics can seem confusing at first, particularly given that the investors are able to calculate the relevant numbers in their heads. The concepts are actually not complicated, and with a few simple algebraic tips you will be able to do the math in your head as well, leading to more effective negotiation.

The essence of a venture capital transaction is that the investor puts cash in the company in return for newly-issued shares in the company. The state of affairs immediately prior to the transaction is referred to as ‘pre-money,’ and immediately after the transaction ‘post-money’.

The value of the whole company before the transaction, called the ‘pre-money valuation’ (and similar to a market capitalization) is just the share price times the number of shares outstanding before the transaction:

Pre-money Valuation = Share Price * Pre-money Shares

The total amount invested is just the share price times the number of shares purchased:

Investment = Share Price * Shares Issued

Unlike when you buy publicly traded shares, however, the shares purchased in a venture capital investment are new shares, leading to a change in the number of shares outstanding:

Post-money Shares = Pre-money Shares + Shares Issued

And because the only immediate effect of the transaction on the value of the company is to increase the amount of cash it has, the valuation after the transaction is just increased by the amount of that cash:

Post-money Valuation = Pre-money Valuation + Investment

The portion of the company owned by the investors after the deal will just be the number of shares they purchased divided by the total shares outstanding:

Fraction Owned = Shares Issued /Post-money Shares

Using some simple algebra (substitute from the earlier equations), we find out that there is another way to view this:

Fraction Owned = Investment / Post-money Valuation = Investment / (Pre-money Valuation + Investment)

So when an investor proposes an investment of $2 million at $3 million ‘pre’ (short for premoney valuation), this means that the investors will own 40% of the company after the transaction:

$2m / ($3m + $2m) = 2/5 = 40%

And if you have 1.5 million shares outstanding prior to the investment, you can calculate the price per share:

Share Price = Pre-money Valuation / Pre-money Shares = $3m / 1.5m = $2.00

As well as the number of shares issued:

Shares Issued = Investment /Share Price = $2m / $2.00 = 1m

The key trick to remember is that share price is easier to calculate with pre-money numbers, and fraction of ownership is easier to calculate with post-money numbers; you switch back and forth by adding or subtracting the amount of the investment. It is also important to note that the share price is the same before and after the deal, which can also be shown with some simple algebraic manipulations.

A few other points to note:

- Investors will almost always require that the company set aside additional shares for a stock option plan for employees. Investors will assume and require that these shares are set aside prior to the investment, thus diluting the founders.

- If there are multiple investors, they must be treated as one in the calculations above.

- To determine an individual ownership fraction, divide the individual investment by the post-money valuation for the entire deal.

- For a subsequent financing, to keep the share price flat the pre-money valuation of the new investment must be the same as the post-money valuation of the prior investment.

- For early-stage companies, venture investors are normally interested in owning a particular fraction of the company for an appropriate investment. The valuation is actually a derived number and does not really mean anything about what the business is actually ‘worth.’

OK… how about a shortcut if there are existing investors and you know both how much they invested and also the percentage ownership they have. Let’s say that investor Z paid $4m for 12% of company Y. This translates to 100%/12% = 8.3 and $4m x 8.3= $33.3m. So from the perspective of investor Z, the company was worth $33.3m at the time s/he purchased the shares.

Valuation and VCs

There’s this dance that entrepreneurs and venture capitalists do when it comes time to negotiate the economic terms of an investment. And it all revolves around valuation.

The question is what is the fair value of the business? This supposedly establishes how much of the company the venture capitalists will own for their investment.

But I think the concept of valuation is often misunderstood by the people engaged in this process. And it’s particularly true in early stage investing.

I do not believe that negotiating a valuation on an early stage venture investment has much to do with the current value of the business. If it did, why would a venture capitalist agree to a $10 million value for a business that will lose money for the next 2-4 years and has little, if any, revenue?

The fact is that almost all venture capital deals are done as convertible preferred stock investments. That means that the money VCs invest is more like a debt instrument in the event the business doesn’t work out very well. VCs get their money out before the entrepreneurs do if the deal goes sideways or down.

It’s only in the event that the deal works out that the percentage of the business (the thing that valuation is supposed to determine) matters in terms of how much money everyone makes.

Another important factor to consider is that only a relatively small portion of early stage venture investments really work out in the way they were supposed to when the investment was made. The following is from a friend of mine and I thought it was brilliant so, I thought I’d share his thoughts here with you – He calls it the 1/3 rule which goes as follows:

1/3 of the deals really work out the way you thought they would and produce great gains. These gains are often in the 5-10x range. The entrepreneurs generally do very well on these deals (the VCs do even better).

1/3 of the deals end up going mostly sideways. They turn into businesses, but not businesses that can produce significant gains. The gains on these deals are in the range of 1x-2x and the venture capitalists get most to all of the money generated in these deals.

1/3 of the deals turn out badly. They are shut down or sold for less than the money invested. In these deals the venture capitalists get all the money even though it isn’t much.

So if you take the 1/3 rule and add to it the typical structure of a venture capital deal, you’ll quickly see that the venture capitalist is not really negotiating a value at all. They are negotiating how much of the upside they are going to get in the 1/3 of the deals that actually produce real gains. A VC’s deal structure provides most of the downside protection that protects their capital.

I think it is much better to think of a venture capital deal as a loan plus an option. The loan will be repaid on 2/3 of their investments and partially repaid on some of the rest. The option comes into play in a big way on something like 1/3 of the investments and probably no more than half of all of a VC’s investments.

There is more to this whole issue of valuation because there are often follow-on rounds where the deal between the venture capitalists and entrepreneurs gets renegotiated. Let’s save that for another time.